Category talk:Political organization charts

Remarks on the charts with the little flags in the above corners[edit]

Dear friends of free knowledge, recently I have uploaded some charts about political systems, or constitutions. Some years ago I have created many articles in German Wikipedia about the political and constitutional history of Germany in the 19th and 20th centuries. At that time, I designed some charts about former German constitutions systems. Becoming unhappy with them, I decided to create new ones.

What follows here is an explanation why I made these charts in the way I did. I also have some suggestions (and nothing more than suggestions) for you, should you choose to use these charts. You may want to translate them into your languages, you may want to create charts about other systems. Of course, you are welcome to give feedback, and I am happy to change charts if you have detected something wrong. Kind regards, Ziko (talk) 14:32, 18 January 2022 (UTC)

The purpose of a chart[edit]

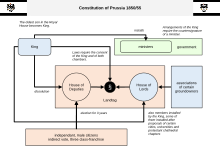

In my opinion, a chart has this goal or task: to quickly show the viewer how the system works and which organs have which main powers. It should be possible to understand, within less than 10 seconds, the relevant actors with most of the power.

A chart can try to purely depict the order as described in the constitution. Or it can be seen as the depiction of the political system that has evolved (on the basis of the constitutional order?). Sometimes, the constitutional law is spread over several legal documents, e.g. a constitional document proper and a law describing the elections to the parliament. Sometimes, an extraconstitutional element or custom is so important that it definitely should be included in the chart.

Given the overall goal, a good chart can be a mixture of both. It may be appropriate to indicate what is an element not found in the constitution, but nevertheless something most important to the functioning of the system. For example, the Dutch constitution does not say that the government has to step down after a vote of no confidence in the second chamber in the parliament. But since the 19th century it would be absolutely unheard of if that would not happen.

What to include, what to leave out[edit]

Reduction is the most important task of a chart maker. A constitutional or political order incorporates dozens, if not hundreds of provisions, elements and customs. A chart becomes unreadable if the chart maker tries to consider too many in the chart.

The center of my charts is the law, symbolized by the law character that I have on my (German) keyboard: §. (Of course, if this is unknown in your language of culture, you can replace it with any symbol that is more appropriate.) The chart should describe which organs decides about the law. The chart should also describe who installs (and dismisses) the government. Usually, the head of state is also included in the chart.

In the many other charts that I have seen, there are usually two kinds of instutions that I have intentionlly left out:

- Courts of all kinds. Certainly they can have a very significant influence on politics, polity and policies. But usually, when the system is normally functioning, the courts are of lesser importance than parliaments and governments.

- The armed forces. I also do not deny that it is important who gives orders to the army, navy and other branches. But in general, it is not a political instrument of power within the political system.

Having this said, it is of course possible that you want to describe a political system in which a court or an army does have a decisive role. A military council or junta may be an example, in which a group of military leaders terrorizes the country and actually decides who becomes a member of the government. Then, this element should certainly be included to the chart.

In German history, the most prominent extraconstitutional elements have been not juntas but extremist parties. An example is the 1949 constitution of the German Democratic Republic. On paper, the constitution does not look very much different from other systems of liberal democracy. In reality, it was the "National Front" (led by the communist party) that created the only list of candidates that was presented to the voters.

The chart for modern Germany is a good example for how to simplify the chart. The Bundestag (parliament) can be dissolved in a relatively complicated procedure involving the Bundestag itself, the federal chancellor (who initiates the procedure) and the federal president (who has the final decision; in practice, that is more of a formality). I chose not to represent it in the chart. Ultimately, in order to dissolve the Bundestag you need a kind of majority in the Bundestag, therefore (and in other cases that a parliament can essentially dissolve itself) I did not put it in the chart.

I understand that some people feel that only a 'complete' presentation is a 'correct' presentation. But actually, we serve the viewers in the best way by reducing complexity.

Design traditions[edit]

In Germany, I grew up with the very popular dtv-Atlas zur Weltgeschichte, and it is obvious that so did many other chart makers from German speaking countries. But the makers of the dtv-Atlas certainly were not the first to establish that, first, the head of state is above in the chart, and the people (voters, subjects) at the buttom.

Other traditional features are the shapes of organs: a head of state is a triangle, a government or court a rectangle, and the parliament is depicted as a circle. (Or, sometimes, a semi circle, comparable to the architecture of some actual parliament buildings.)

I chose the circle for parliaments and similar (larger) organs but did not adopt the triangle for heads of states. The triangle turned out to be very impractical as a geometrical element in a chart; it is difficult to place text in it, and it attracts a degree of attention that is not justified in all political systems.

Furthermore, I dumped the tradition to divided the chart in three parts. In the tradition, each third is used for one of the three powers as described by Montesquieu. I found this division to be very impractical. Another concern is that the division in three powers does often not do justice to a political system.

For example, traditionally we call the government (cabinet) a part of the executive and the parliament a part of the legislative. But in many political systems, the government has also a legislative function. It can propose laws to the parliament, and actually the large majority of laws are these (at least in Germany and other systems that I know).

Color and lines[edit]

There are numerous charts that use color extensively, and also different kinds of lines. In general, I did not want to use too many colors. Finally, I use a pale red tone for the people and parliaments, and a pale blue green tone for executive organs. A pale blue serves for heads of states and other organs that are not clearly a kind of parliament or a kind of executive organ.

The boxes and circles have always the same (black) line thickness. The thickness of the arrow lines is a different one. All arrows have the same shape.

I decided against different colors and styles for lines. Many charts have them, but they are used in many different ways. For example, it seems that a dotted line does not have a 'natural' meaning that is intuitively (and universally) understood. Also: you need a legend that explains which line style or color has which meaning; the readers would have to learn something before they can understand the chart.

Using captions[edit]

It turned out to be much better to describe an element or an arrow with a caption, a short text description. For the readers/viewers of the chart, it usually is much much easier to quickly read the caption instead of looking down to the legend and try to figure out what that color and that shape/style may want to suggest in the given context (elects/appoints etc.).

A caption can also be handy to avoid drawing a line across the whole chart. You just mention a particular power or function in a caption explaining an organ. This should, though, be the choice for minor powers.

How to create or translate a chart?[edit]

For the charts I used the LibreOffice software, or more precisely, LibreDraw. It is free, gratis, open source software. It has a major advantage compared to MicrosoftOffice products such as Powerpoint or Publisher: LibreDraw can save (or actually: export) your drawings in the SVG format. This makes it possible to download the SVG file from WM Commons and change the drawing.

For example, if you want to translate a chart, you download the SVG file to your computer. Then you rename the file: replace the 'EN' at the end if the title to the language code of your language. Or, for example, if you want to translate a Dutch language chart to French, replace the 'NL' with 'FR'. Keep the title of the title in English.

Then open the file. Change the drawing as you wish. If a caption field is too small for the translated text, then enlarge the field (or try to translate it in a different way). At the end, save the file. You can now upload it to WM Commons. Please add one file description in English language and another file description in the language that has been used for the chart. This will make it easy to find the chart in English, but also for people who are searching WM Commons in the language in question. Please add a category by country, e.g. 'Political organization charts for France'.

In general, it is a good thing that the charts are usually similar to each other. That makes it easier to compare systems. Nonetheless, sometimes a system requires some larger changes, for example to include a third chamber or to present a complicated organ.

Good luck! Ziko (talk) 14:32, 18 January 2022 (UTC)